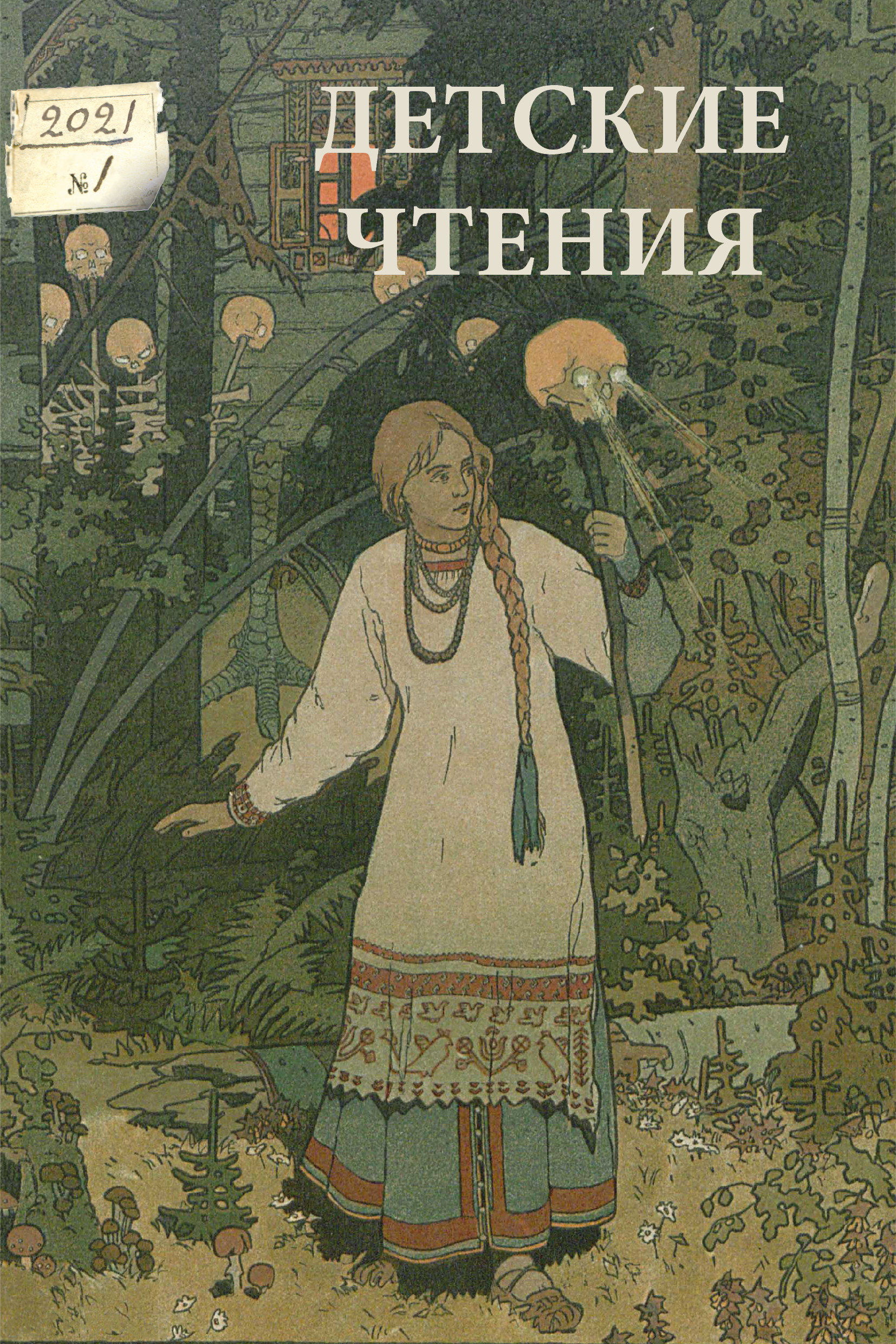

A tale? A lie? A lesson? On some quasi-literary debates about the (lack of) usefulness of a genre

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.31860/2304-5817-2021-1-19-8-43Abstract

During the last two decades, a series of publications drew scholars’ attention to the institutional and ideological context in which the politicization of the fantastic, animistic, and magical took place in the USSR in the late 1920s. In these narratives, «the fight against chukovshchina» is often used as an epitome for the «fight against skazka», which was orchestrated in 1928 by ignorant officials from the Narkompros and aimed at a small group of authors lead by Kornei Chukovsky.

Important as it was, «the fight against chukovshchina» was a small and, perhaps, the least intellectually interesting aspect of the ongoing discussions. Debates about skazka did not start in 1928. Nor were they purely Soviet. Similar themes, arguments, and concerns could be easily found in the polemical exchanges in literary and pedagogical periodicals from the 1860s onwards. Key ideas and approaches that were articulated in the 1920s-1930s by and large repeated and repurposed the ideas that took shape long before the Bolshevik revolution.

Expanding on the existing scholarship, this introduction to the archival collection «Debating Fairy-Tales» takes the scholarship on skazka beyond the institutional and ideological analysis in order to look closer at the intellectual context that shaped early soviet debates on the limits and function of the fantastic imagination. As the introduction suggests, when read this way, the debates on skazka show how this particular genre was deployed as a platform that enabled a series of fascinating paradigmatic shifts in understanding the links between national literature, on one hand, and education and imagination, on the other.

By locating the early soviet debates on skazka within a much larger temporal frame, we could destabilize the monopoly of «the literary studies of politics» in order to see how skazka was conceptualized and problematized within radically different intellectual traditions — from the genetic and the functionalist to the morphological and the rhetorical. Such a diachronic approach makes visible how the original concern of the critics with the problem of skazka’s own origin was replaced by their attempts to figure out skazka’s functional purpose, it’s own internal structure, and, finally, the forms and types of skazka’s impact on it’s readers.

Keywords: Humanities debates, pedagogics, realism, imagination, soviet theories of reading, genre studies